The awakening of worker cooperatives in Europe

Europe is currently experiencing a revival of cooperativism and in particular that of worker cooperativism. Despite the fact that cooperatives are invisibilized through the "Social Economy" discourse, thousands of workers in France, Germany, Italy or Spain, fed up with the precariousness of life and work and the absence of solutions proposed in increasingly divisive and aggressive discourses, are overcoming passivity, confronting atomization, organizing productively, joining their families and communities and collectively taking the future into their own hands.

The modest but steady growth of worker cooperatives in Europe before the war

Everybody forgets about Santa Barbara, the patron saint for protection of bad storms, until it thunders. Before the pandemic, when it seemed that the European economy was going to recover and enter a new phase of growth, worker cooperatives had lost the interest they had generated among academics and social activists in the years of so-called millennial politics.

Nevertheless, the number of new worker cooperatives continued to grow at a steady pace: about 300 per year in France, more than 1,000 per year in Spain; even in Italy, where the local branch of the ICA invisibilizes worker cooperativism at a remarkable level and where no specific statistics on them are published, there were already then about [16,000 worker cooperatives which generate almost 40% of new cooperative employment](https://euricse.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/2023.06.19-Rapporto-Italia-editato-finale_web.2 .pdf) (including banks, mutuals and social cooperatives, which alone generate another 39.3%), data only surpassed by Spain which with 18,941 worker cooperatives supporting 319,039 worker-members remains the champion of worker ownership on the continent.

The war in Ukraine and de-industrialization

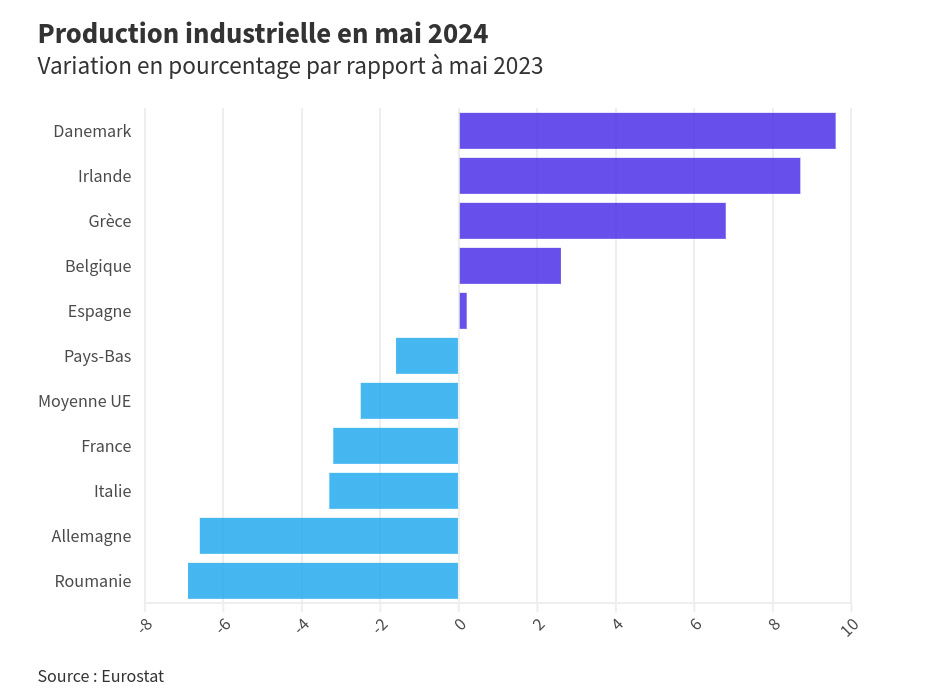

After the pandemic, the war in Ukraine opened up a period, which we are still living in, of rising energy costs, capital flight to the USA and deindustrialization across the continent. In the graph above, we can see the fall in industrial production between May 2023 and May 2024 in France, Italy, Germany and Romania (the intra-European China of French industrial investments). Countries that increase their production by similar percentages are far from compensating in absolute terms for the loss.

The result has been a wave of bankruptcies of exporting SMEs that started in Germany and, in turn, an epidemic of closures due to retirement. Across Europe there is a generation of owners who, despite having survived the current wave of bankruptcies, are too old to make plans for the future but are unable to find buyers at a time when not even Mario Draghi is willing to work to ensure the continuity of their businesses in a competitive environment that European capital already considers lost to China.

Worker cooperatives as a response to the abandonment of businesses

It was then that sectors of German employers began to view corporatist models of foundational ownership (Social Economy in its pure state) as a managerial alternative to the purchase of the company by the workers themselves and the cooperativization of the companies, the latter being a reality that was beginning to be considered a solution to the abandonment of the company by the business owners in Italy and France.

In Germany itself, there was no lack of successful examples in which the heir and buyer were the workers themselves, organized as a worker cooperative. Iteratec, a well-known Munich software company with 500 employees at 7 workplaces and a turnover of around 70 million euros per year, was being converted into a worker cooperative by its founder. The attraction of the cooperative model was making an impression even among the winemaking families of the Palatinate, a paradigm of German conservatism.

Worker cooperatives as a solution to the bankruptcy of benchmark industries

However, the problem that is most painfully perceived socially in Europe is that of the closure due to bankruptcy of relevant industries. Here, too, there is no shortage of examples. La Meusienne, a company in the Meuse, the French industrial region bordering Belgium, founded in 1899 and which is currently the last open pipe manufacturer in the entire country, was bought by its workers last July and converted into a SCOP (Société Coopérative Ouvrière de Production).

This is not an isolated example. In the regions which are suffering the most damaging deindustrialization, such as Alsace, examples abound. As the leader of the local branch of the ICA commented to the press, the number of SCOPs has doubled in the last five years.

The "rescue" of Duralex and the public acceptance of worker cooperativism as an alternative to closures

But the case that has put worker cooperatives at the center of the hopes of many in France and Europe was that of Duralex.

Formally declared bankrupt by the judges in April this year, the company, a symbol of durability and unbreakability, had been floundering for twenty years, passing from hand to hand without any of the new owners - the last was Pyrex, in receivership since 2021 - investing what was necessary in order to renew the catalog, the machinery and the image of the company.

Duralex received three purchase offers. The most attractive offer at the time was that of Tourres et Cie, owner of La Rochère tableware and Waltersperger, the factory that produces the bottles for many of France's high-end perfumes. Their offer consisted in maintaining 179 of the 228 jobs at the glassworks and was supported by the union CFDT, once an advocate of worker self-management. On the other hand, 60% of Duralex workers supported in assembly a proposal to transform Duralex into a worker cooperative, which entailed the conservation of all the jobs, and they accepted to pay a slightly higher price than the other two companies.

Duralex, a global brand and symbol of the good old days of French industry, received a considerable amount of media attention, which served to gain the sympathy of a significant part of social opinion... and thus obtain the support of local and regional governments, without which the banks would not have financed the workers.

When the judges finally ruled in favor of the workers' offer, Duralex was already a new French symbol, or rather, the symbol of a new France. As a result, online sales of Duralex multiplied during the first days, long before the first retail orders arrived.

The worker cooperative as an inspiration for a post-neoliberal and post-identitarian policy

The France that re-adopts Duralex is the France that is watching The Fever and supporting, with all its contradictions, the New Popular Front to stop the rise of the lepenist extreme right. It is the France that the Jaurès foundation is trying to understand by commissioning two dozen papers from academics analyzing the series.

What the think-tank foundation of the Socialist Party discovers among papers and opinion studies is that, the cooperative in general and the worker cooperative in particular are becoming the alternative to the divisive and identitarian discourses of racialist indigenism, neofeminism and identitarian xenophobic nationalism. That is why it points out that the New Popular Front must, if it wants to serve as the basis of a post-neoliberal and post-identitarian left, organize itself in the manner of a federation of cooperatives through a model proposed by François Ruffin himself in a television interview on prime time in which he defined himself as a social democrat for the first time.

What is interesting is that at the same time as Duralex in France, other European countries are experiencing phenomena similar to those reported in The Fever. In fact, reality surpasses fiction: the Sant Pauli FC, created in 1910, became a community cooperative in a similar way to that of Benzekri's series. According to the German sports press:

They [the managers behind it] want the founding of the cooperative to be seen as a “counter-proposal to the power” of the big investors and “their betrayal of soccer”.

Sant Pauli has great symbolic power, linked as it is to the Hamburg dockers and port workers and by being recognized as the anti-Nazi club during the 1930s and above all by representing the last bastion of soccer romanticism in the Bundesliga. Its cooperativization immediately attracted the attention of the mainstream media and became a trending topic throughout the German-speaking world. The impact multiplied to the point of getting the Austrian government to promise to change the law on sports societies so that Austrian clubs can follow suit.

With the whole world watching, Sant Pauli soon looks like a reincarnation of the Corinthians of Socrates, Wladimir and Zenon in the middle of the North Sea. The fortune of the team had changed as a consequence and it began to score goals away from home.

Suddenly community cooperatives gained the attention of the German press and a whole underground and community cooperative movement driven by municipalities abandoned by the healthcare system, as well as towns that want to ensure universal and low emission heating, retired people who do not want to have to go retirement homes and thus organize themselves to share housing amongst each other and nurses and families who want to organize home care for the elderly, starts to appear in newspapers all over the country. Within this wave that we are now experiencing, quite a few worker cooperatives are beginning to define a new paradigm of success that is very different from that of the start up entrepreneur: historians who want to make a living from being historians, cooks and waiters who create family restaurants with a logic similar to that of cultural centers....

Neither bought nor "rescued": what are the new worker cooperatives in Europe like?

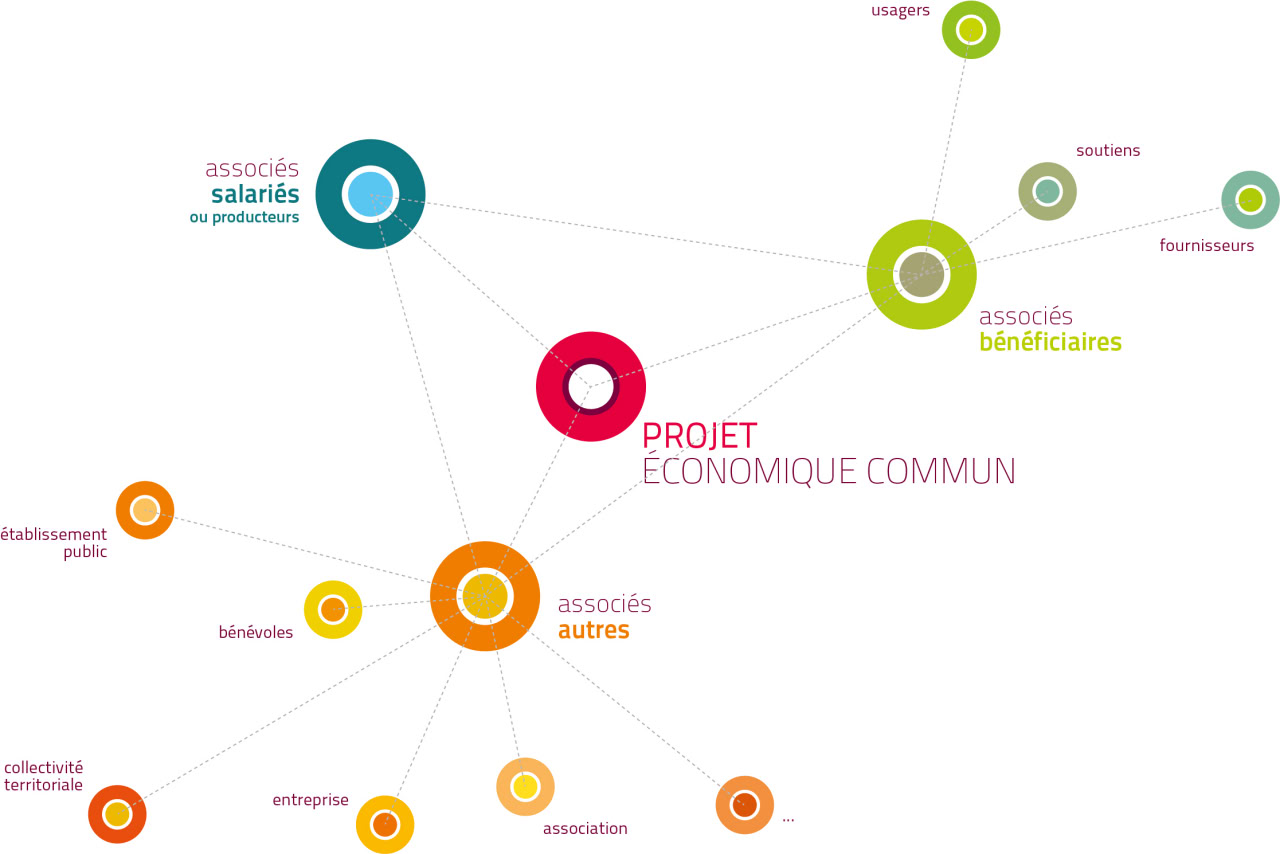

Because even if Duralex, La Meusienne, Iteratec or Sant Pauli have become the symbolic engines of the cooperative awakening we are experiencing in Europe, the protagonism of the creation of worker cooperatives is not in takeovers nor in recoveries after bankruptcies.

In France, in 2023, only 8% of all SCOPs were the result of the acquisition of an enterprise experiencing difficulties and only 13% of a healthy enterprise. Sixty-one percent are newly created companies. The typical profile of new SCOPs is a digitized service sector company founded in a medium or small city.

In Spain, where 319,039 worker-members of 18,941 worker cooperatives produce 5% of the GDP of the fourth largest economy in the EU, 78% of newly created worker cooperatives are in services, 13% in construction, 7% in industry and only 2% in the agricultural sector. Even in the rural world, worker cooperativism seems to be concentrated in the service sector.[1].

[1]: In a recent COCETA study on worker cooperatives in the rural world the statistical sample taken by analysts shows that 16.9% of worker cooperatives are in the tourism and hospitality sector, 12.5% in cultural activities, 5.2% in advanced services such as consulting or information technology and only 12.8% in agri-food production, 4.1% in livestock, 2.8% in forestry activities and less than 2% in milk or cheese dairy. We do not know to what extent this sample is representative of the real total. For example, the fact that only 13% are dedicated to “cleaning and social services” is striking when compared to the CEPES study on “Care from the Social Economy”, which states that the Social Economy sector in the Care Economy totals 3,139 companies and entities, of which 79.4% are cooperatives. The differences are probably due to the definition of “rural environment”, which varies from one study to another..

An interesting fact in both countries: both in France and in Spain worker cooperativism grows in a way that cannot be predicted neither by looking at regional GDP per capita nor by population. In other words, the experience of cooperative work goes beyond territorial differences and divergences.[2].

[2]: In Spain in 2023, for example, 24.5% of the members of new work cooperatives were in the Valencian Community, 17.8% in Andalusia, 11% in the Basque Country, 9.1% in Catalonia, 8.7% in Galicia, and 8.4% in Murcia.

The European “cooperative awakening” is now

Unlike what happened in the years of “millennial politics”, of the “occupy movement” and the movement of the “indignados” (the outraged), the attention being placed on the cooperative world we are living now is not based on personalistic mythifications and the spectacular games of the media, but rather on spontaneous and independent collective and communitarian experiences. We are not talking about a narrative or discourse replete with examples, we are talking about a social and economic reality that shoots out in the macro data.

Its promoters are also not more or less bohemian and rebellious students and young people inspired by a new generation of gurus, but rather normal workers of all sectors and ages - bricklayers, computer scientists, sanitary workers, consultants.... Their scenarios are factories with deliveries to attend to and real clients, offices with potted plants more akin to a coworking space than a busy social center, and bars and cultural centers that on Saturday are filled with families.

Therefore, what we are living now is not fun from the point of view of communication experts. It is not like in the 2010's when integral cooperatives were constituted as a representation of a desire, which an academic-media environment eager for examples spread as if it were tangible reality and as though a revolution would have started without us even realizing it. Neither the desire was reality, nor was there a revolution underway, and the contradiction could only lead to melancholy and frustration.

Today we are not living a revolution either. Only - but it is no small thing - a cooperative awakening: a moment in which thousands of European workers, fed up with the precarization of life and work and the absence of solutions proposed in increasingly divisive and aggressive discourses, are overcoming passivity, confronting atomization, organizing productively, bringing their families and communities together and collectively taking the future into their own hands.

And yet, despite the apparent force of the numbers and the contagious enthusiasm of the protagonists, it is a flower that is vital for the immediate future and also a delicate one. It cannot grow on its own with the admiration of others. It needs soil and irrigation. It needs a committed environment and new cooperativists and cooperatives. It needs work. It needs your imagination and your willingness.