Accounting for commoners

Accounting is imbued with ideology, but it also provides valuable information. Understanding the former and applying the latter are essential in order to increase the viability of worker cooperatives, social projects, associations, foundations, etc.

A long history

Origins

The invention of accounting can be traced all the way back to the start of civilization, most likely during the later phases of primitive communism, around 7,500 BCE. Accounting at the time was used to record the stocks of stores and livestock of the commons at a time when nomadic communities were already large and which would only meet with each other during a certain time of the year in what would become the first cities.

Later, around 3500 BCE, both in Mesopotamia and Egypt, in the new cities, already permanently inhabited and divided into classes, these forms of accounting and primitive writing would become more sophisticated. With the emergence of social classes and the state, accounting - and writing - had acquired a new use: recording the payment of taxes.

The word pay, which derives from the Latin pacāre, to appease, is reminiscent of a time where those payments were not used to exchange goods, but rather were the product of an armed threat which shaped the first forms of exploitation of the labor of others. The other word we use today as a synonym for tax, tribute, refers to how the original tax subject was not the individual nor the family, but rather the subjugated tribes. The royal houses had thus granted a systematic character to the exemptions they demanded from the communities they had previously subdued by force. The royal houses constituted the first State and were in reality nothing other than the head of the warrior class, which in turn, in most cases, was probably nothing other than a conquering people.

In Sumer, Egypt, the Indus Valley and China, this type of record-keeping would be extended over time to new areas. For example, the control of the arrival - also taxed by the state - of inputs in the cities and payments made by the royal treasury to those pockets of artisans and free laborers whose work they would employ in a very limited way.

However, this first accounting system bore little resemblance to the current one. They were not much more than a series of inputs and outputs of goods from the royal stores, carried out by the first state bureaucracy as part of an early attempt to systematize the government of the brand new ruling classes, a novelty in the history of a species that had been living 350,000 years without them.

Roman accounting

Until the consolidation of the Roman Empire and with it that of a fluid and continuous trade in the Mediterranean, the way in which a commercial operation or business was accounted for had not changed substantially. However, trade was limited in scope. The only potential buyers were the state itself and the free classes, which, although they made up the majority in the large city centers, they were in the minority in the territory as a whole. Trade could thus only reach a minority within the slave-owning society.

Moreover, Roman distance commerce, the real framework of the limited system of mercantile exchanges, was monopolized by the patrician class. That is, the great slave owners, who also monopolized merchant fleets, the sales of grain to the state and the factories of wine, oil and luxury goods in the provinces. An example of a luxury good produced during this period was garum, the well-known sophisticated industrial fish sauce that materialized the first territorial division of labor over long distances.

In reality, the most that the plebeians and the lower free classes could aspire to do with trade was to get a slave to attend to a tendum, a market stand, in order to either sell what they had produced themselves, if they were artisans, or what they purchased from the patrician houses.

And above all, commerce was not considered the source of social wealth, but rather the countryside, which fed the entire society and whose regular supply was the basis of social peace and therefore of the power of the ruling class.

That is why no patrician was going to boast of its ability to gain profits or make good commercial deals. On the contrary, even if trade offered them an economic benefit, it remained outside of their function and objective as a class, that which gave them prestige among their equals and recognition by the state in which they directed social work, carried out in its vast majority by slaves.

Therefore, the advances in Roman accounting were also due to the importance of agricultural management, rather than trade. As Rome expanded, the patricians, who spent more and more time away from their rural villas, engaged in political struggle and the expansion of the empire, ended up delegating day-to-day management of their land to highly skilled, freed slaves.

The slaves were in charge of the day-to-day tasks of the household, understood at the time to be a productive unit, and had to submit their calculations to their masters on a regular basis. The word calculation comes from the Latin word calculi, which were the stones or beads that were used, not only for board games, but also to add and subtract. These calculations, which were then presented as a sign of good patrimonial government and therefore of the respectability of the head of the family, were compiled in two books. The Codex and the Adversaria.

The Codex recorded the inflows and outflows of patrimonial wealth, the reason for them and the amounts involved. Most of these transactions, however, lacked a monetary nature. The birth or death of slaves, the grain consumed to feed the labor force and the owning family, the harvested production and even the payment of tribute, regularly and substantially modified the patrimony, but did not involve the use of currency or any form of exchange. The Adversaria, on the other hand, recorded income (Acepta) and expenses (Expensa) and the total amount of "cash" in legal tender.

When this system of control and reporting was applied not to a normal farm, but rather to a commercial business, the result resembled the double entry system that would become widespread in Europe at the end of the 14th century. But, as commercial activities at the time played a marginal role in the economy of a typical patrician family, this form of administration did not survive the collapse of Mediterranean trade that accompanied the crisis of the Roman Empire. With the development of feudalism from the 4th-5th century onwards, systematic accounting virtually disappeared from the life of the new Christian European ruling classes. And when it would return, with Charlemagne, it would do so in the form of a catalogue of inflows and outflows of funds and goods from royal stores, in the old style.

Why did “accounting” barely develop during such a long period of time?

Everyday life before capitalism was very different from the way novelists and television screenwriters portray it. They feel very comfortable with developing plots rife with scenes in taverns and markets where the protagonists buy all kinds of goods. Whether set in ancient Egypt, classical Rome, feudal Europe or, in their fantasy version, in worlds of dragons and dungeons, we can always count on the protagonists of these stories to be in possession of a bag full of gold or coins, the contents of which they will exchange for goods and services in the places they pass through.

But reality bore little resemblance to that fictional depiction of the past. Up until the end of the 18th century, with the establishment and spread of capitalism in Europe, the scope of markets was rather sparse and the widespread exchange of goods was a pipe dream for most of the population. To begin with, the vast majority of productive labor was performed by people, first slaves and then serfs, who neither received a wage nor could sell anything of their own. And since they could not even go out to the market to sell their capacity to work, they could not resort to the market to buy anything either. It was only from the 12th century onwards that they began to be able to exchange some crop surpluses, usually by barter.

However, in the construction camps of ancient Egypt or in the mines of Sierra Morena under Roman rule there did in fact exist some pockets of salaried workers, despite the fact that slavery played a central role in the economy. But these salaried workers weren't anything more than pockets, that is, more or less rare phenomena intended to alleviate temporarily and on a local level the lack of slaves. The tendum that we find in ancient Roman cities and the later medieval markets that are celebrated so much today, had a very restricted public: that of the possessing classes. Moreover, if most labor was not yet commodified - that is, the capacity to labor could not yet be bought or sold - neither could the possessing classes freely buy and sell the other great productive factor of the time: land.

That is to say, the scope of mercantile exchanges was, until relatively recently, very limited and in some epochs, which in Europe lasted centuries, practically nonexistent.

The rise of double-entry accounting

From the 4th century onwards, Christian Europe saw a gradual reduction of mercantile exchanges until the minting of coins practically disappeared. The remaining coins were thus no longer being invested - since neither land nor labor force could be bought nor were commercial expeditions being paid for - and at best were being accumulated.

Meanwhile, a true golden age of long-distance trade has been underway in the Muslim world since the 9th century, weaving business networks from the Gulf of Guinea and Mali to China. To overcome the difficulties and risks of transport and roads, Muslim merchants created new financial tools such as the check (shej) or transfer systems (hawala).

However, by the end of the 11th century, a new class of merchants began to appear in Europe. At first they would be almost indistinguishable from highwaymen. They were referred to as pedes pulvorosi (dusty feet), but little by little they would group together and settle around burgs and villas. They are the ancestors of the villains of the literature of the Golden Century, the first bourgeois. Having their start in minor trades and on the margins of feudal society, this new class, the bourgeoisie, would, over the course of four hundred years, build power in the cities and tear Europe apart with increasingly extensive routes and markets that would serve as a skeleton for the first continental industries, such as wool.

It seems that it was the Jewish merchants of North Africa who were the first to connect these networks with the Muslim ones, lending them financial tools and organizational forms. From then on, merchants would take control of artisan guilds, subordinating their production to the needs of long-distance trade, and would also create the basis of the first banking system, which was in fact named after the benches (banki) that the money changers and enforcers of the law of currency placed at the entrance of fairs and markets.

This new class, living full time in a mercantile economy and which continued to represent a minority in the world at the time, would engage in increasingly complex credit operations - the word credit comes from the Latin word credere, which means to believe, to trust - and would rely more and more on agents and associates in distant ports and markets. Controlling and overseeing these agents became the obsession of most large merchants. Especially in the decades following the Black Death. From then on, serf revolts and the intensification of the class struggle throughout Europe would call into question the idea that everyone should know their place. We are talking about a cultural change that reflected the rise of the bourgeoisie... but which did not make things easy for it when it would come to recruiting reliable agents.

The most serious attempt to achieve this would be to systematize accounting by incorporating double entry accounting, a system in which the need to match the balance and explain each expense with an equal income demanded a rigorous control of inputs and outputs by agents. The new accounting system would become the norm in the Mediterranean in the 1390s.

A little more than a century later, in 1494, the Franciscan Luca Pacioli - a mathematician as well as magician, art theorist and alchemist - would publish his Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita. The book was a compendium of the mathematics of the time and included a treatise on algebra and arithmetic. But Pacioli was writing for Venetian merchants, who were to use his work as the basis for the education of their children. That is why it was the first mathematical book written in common parlance. For the very same reason, he incorporated currencies, weights, and measures used in the different Italian states and regions in his arithmetic. And to top it off, Pacioli did not hesitate to add a 26-page capitulito entitled Tractatus de computis et scripturis.

This was the first theorization of double entry accounting. If it was designed to train the children of the new and powerful commercial class, accounting had to be theorized and systematized as the art of the new era.

The conception of the company that arises from applying these standards is revolutionary. It clearly marks the difference with the Roman patricians' view of their houses and families as a productive unit. For the patricians, patrimony is everything, for the bourgeoisie the enterprise is nothing; it is merely a shell with nothing of its own inside. Everything the enterprise has it owes to someone: to the owners, who put up the capital, or to third parties to whom it is indebted. Everything it receives is subtracted by an outflow of equal value. Everything it sells is subtracted by a payment.

The world portrayed by double-entry bookkeeping is a world in which there is nothing but mercantile exchanges between individuals, exchanges of equal values that end up magically producing a surplus... equal to the debt of the company to its owners. The world seen through the lens of double-entry bookkeeping is the first circulatory utopia of the bourgeoisie.

Let's dive into how this would work in practice by looking at the balance sheet of a cooperative today through the lens of a medieval merchant... or an auditor, because the system in reality has not changed since then.

The Two Key Documents

The Balance Sheet

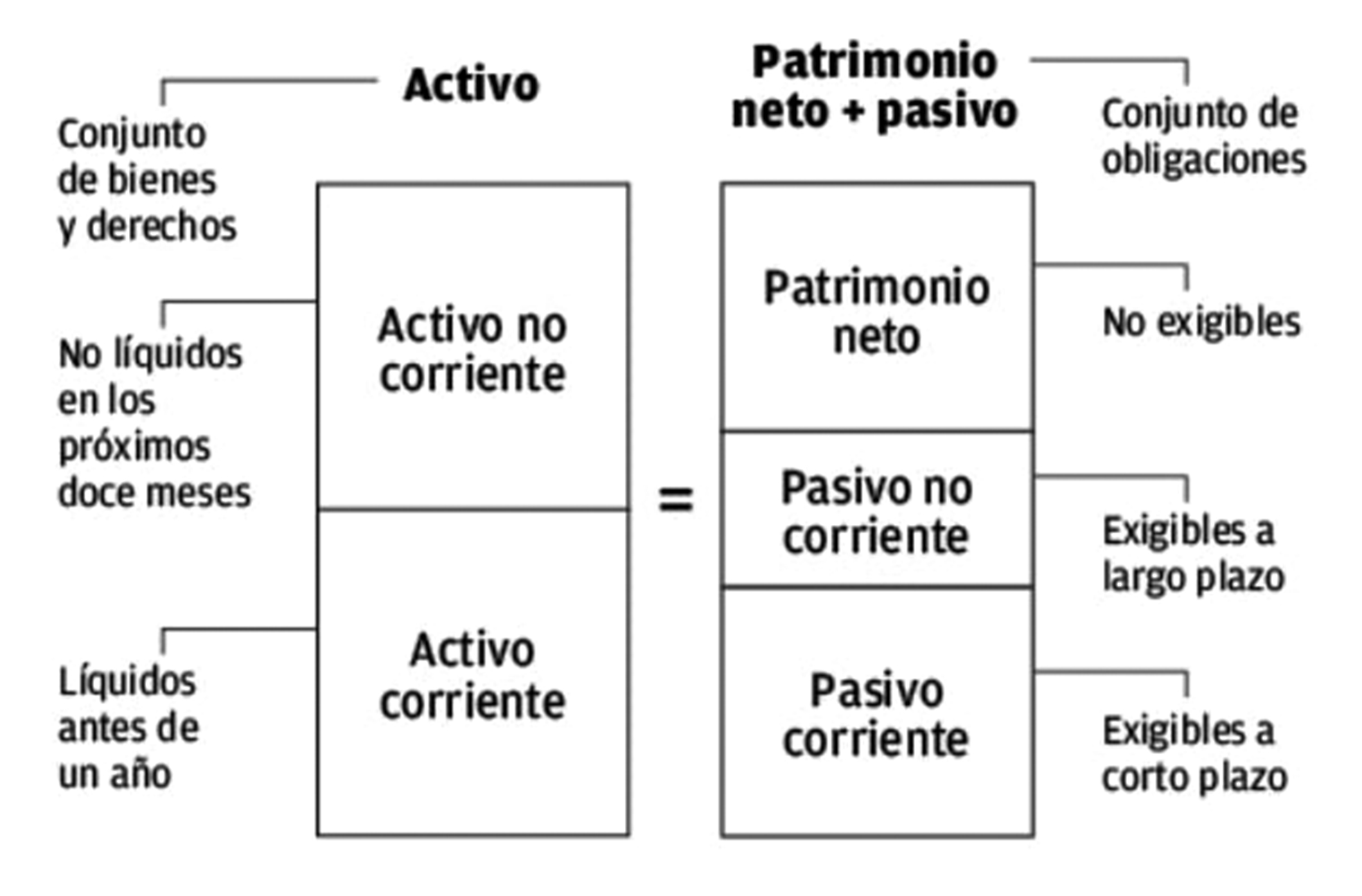

In a world in which the logic of accounting inherited from medieval era merchants dominates, the assets of the company, what it has, including debts owed to it by others, is equal to the sum of its patrimony, which in theory belongs to the partners, and its liabilities, which is what it owes to third parties.

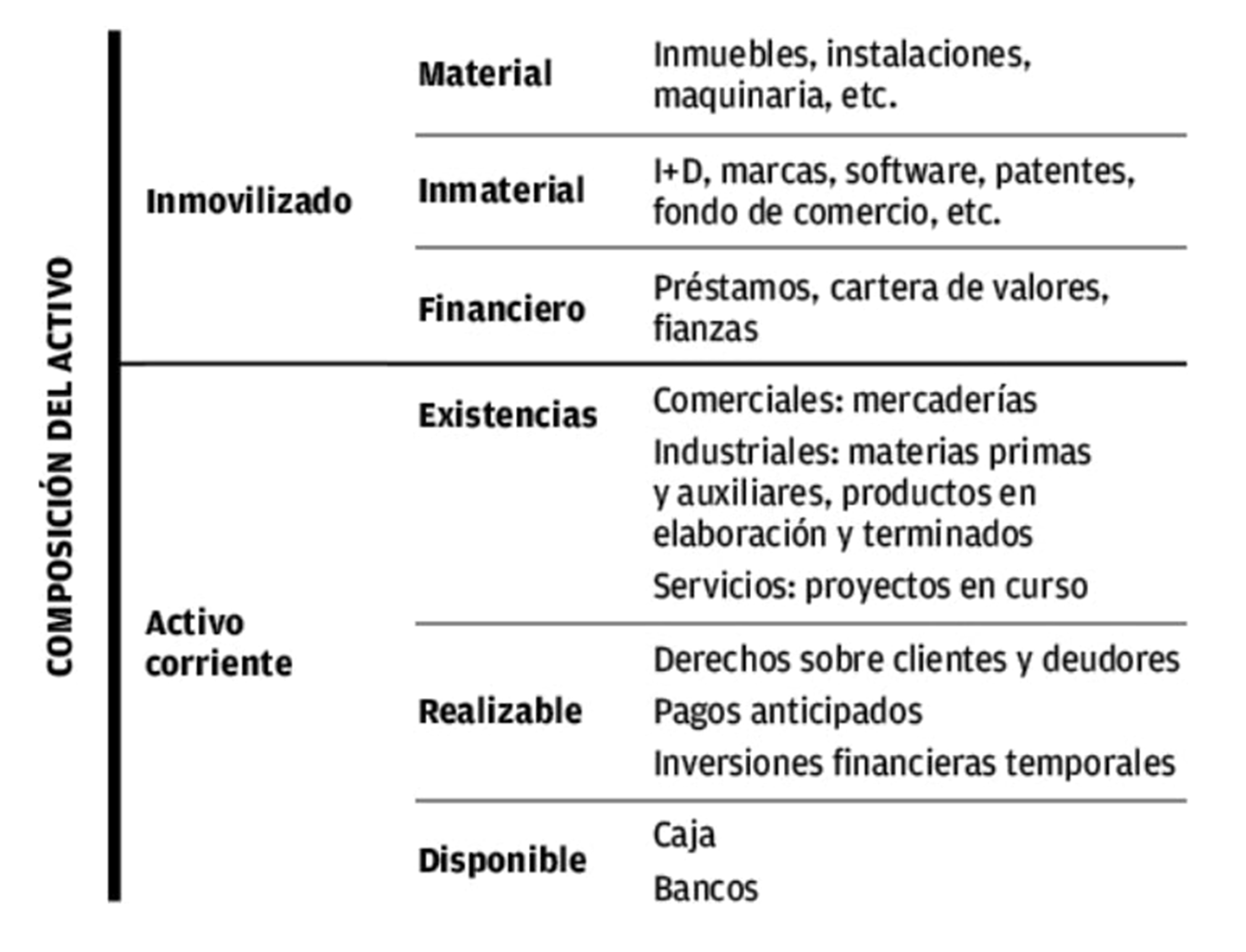

Assets are ordered according to the liquidity criteria: what is expected to be converted into cash within a year - for example, an outstanding invoice - would be categorized as current assets- while the rest, whether it be a property or a term deposit etc., would be characterized as non-current assets or fixed assets. The distinction matters because current assets are used to pay bills while non-current assets are immobilized and are not useful for saving the company from pitfalls or for paying short term debts.

Current assets are further divided into stock (goods, materials, etc.), marketable security (shares bought for speculation, short-term debts that others have with us...) and cash or cash equivalents (the money we have in current accounts, cash, etc.). Fixed assets are divided into the following categories: tangible (premises held in property, machines, vehicles...), intangible (permissions, patents, licenses, etc.) and financial (loans that we gave to others, investment shares, the rental deposit of a ship).

Let's take a look at this table.

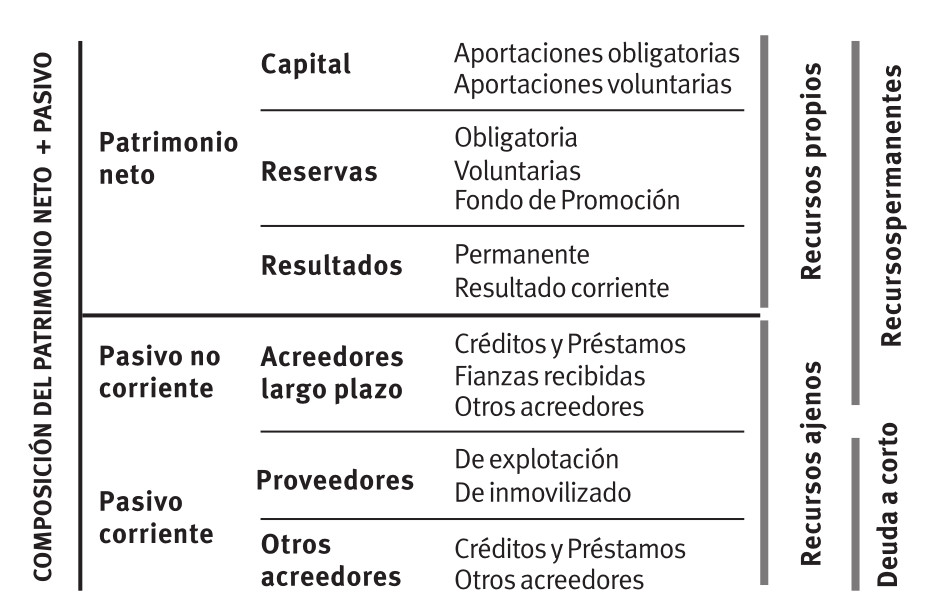

In the same way, liabilities and equity are arranged according to their demandability, i.e., in order of the maturity of the company's obligations to others, and are also divided into several categories in line with their nature.

By putting one thing and the other together and returning to the original scenario where there is nothing but exchanges of equal values, we get the famous balance sheet.

The balance sheet compares what the company has with what it owes. Following the logic of the merchant overseeing their agent, we have to list both of the things that the agent declares on the balance sheet and make sure that the results “balance out”, i.e. give the same result on both sides. The total of what the company owns, the assets, has to equal what the company owes to the assets plus what it owes to others. The result changes with each transaction, that is why the literal translation of the term "balance sheet" in Spanish is "the balance of the situation" because the outcome will be different at each moment.

The profit and loss account

The other essential document is the profit and loss statement. It records only revenues and expenses and evaluates the company's performance during a period. You can't see here whether or not sales have already been collected and whether or not we have paid for the raw materials we bought. It is about whether the business is working or not and why.

| Income | Expenses | Performance (Income - Expenses) |

|---|---|---|

| Revenues. Revenues from sales of whatever we produce, whether tangible products or services. If we have several lines of business, they will be of different types. | Cost of goods sold (cost of sales). When we sell industrial products, it is the raw materials, logistics, etc. When we sell services, it is the workers' wages and salaries. | Gross profit or operational profit |

| General operating expenses (structural costs): rent, water, electricity, insurance, the professional services of external providers (accounting, marketing, etc.) | Operating income | |

| Extraordinary income. What is not the outcome of cooperativized work, i.e., what is not covered by the economic activity described in the corporate purpose, except for financial income. | Extraordinary expenses. Irregular expenses that occur in an unforeseeable manner. These are for example losses from the sale of a machine or a car, product losses due to an accident or a flood, etc.. | Earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) |

| Financial income. Those produced by interest from bank accounts, dividends from investee companies, etc. | Financial expenses. Loans, credits... and in the case of a cooperative the remuneration of voluntary and obligatory contributions if the bylaws permit it. | Profit Before Taxes (PBT) |

| Corporate income tax. The surplus tax levied by the state. | Net income |

We have added a third column to obtain from these categories the different outcomes of the company.

- Revenues - Cost of goods sold = Gross profit.

- Gross profit - general operating expenses = Operating income.

- Operating income + extraordinary income - extraordinary expenses = Earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT)

- EBIT + financial income - financial expenses = Profit before taxes (PBT)

- PBT - Corporate income tax = Net income

This obeys the logic of placing large bundles of idle capital in businesses with an extremely high level of capitalization. This is what the so-called Internet “unicorns” do, whether it be Google or Amazon or Uber or Zalando, to present some examples. They invest gigantic amounts of capital - whose amortization weighs heavily on earnings for years - in order to create barriers to entry for competition.

Who would invest brutal amounts of money to outperform an established business that does not make a profit? Speculators with few means of investing large funds in the hope of achieving a profitable monopoly in ten years' time. How do they evaluate whether the business is profitable and will leave good profit margins in a few years? By eliminating depreciation and amortization from the calculation. Hence the EBITDA trend.

In a nutshell: EBITDA is useful for calculating business income if the business consists of generating a monopoly through the intensive use of capital. If EBITDA is applied anywhere else, whether it be the local hairdresser's, the online newspaper, or the oil mill, it only serves to confuse and can lead to ignoring costs that could make the company's activity unsustainable. These smaller companies also have the added disadvantage of lacking access to the support of a speculative fund.

How would a medieval merchant read accounting documents?

Big auditing firms and their offspring, consulting firms, come from an accounting tradition that merges with the history of the birth of financial capital in the United States. Their objective has been streamlined to the point where its focus has become an updated version of the medieval merchant's conception of the company. The medieval merchant's conception of the company - that is, where the company owes everything it has to the owners - was innovated to the point where it had become the paroxysm of the slogan generate value for the shareholder.

Translation: the entire management of the company is reduced to increasing the speculative value of the shares in order to attract as much capital as possible. Ultimately, the question that the company reports are intended to answer is: how to sell the company to idle capital funds for the highest total amount possible.

The indicators they use, such as EBITDA, ROI (Return on Investment) or ROE (Return on Equity or financial profitability, the ratio between profit and net worth), are conceived from the point of view of capital seeking placement, which is not that of the normal company, the associative project or the worker cooperative... unless its owners want to get rid of their project or company at the best possible price.

The outcome of this type of management is well known: at first glance, the company's indebtedness will increase. As more capital is employed, the shareholder should expect higher dividends - more profitability - seeing that more capital is employed. Then the consultant will use the fragilizing scythe which consists in the reduction of operating costs, wages and inputs, which logically lead to the outsourcing of entire parts of the production process and to the reduction of product quality, to point of being low cost, and the radical de-skilling of workers, that is to say, the loss of something extremely valuable: knowledge. Between outsourcing and gross profit margin increases, EBITDA, ROE and ROI end up inflating... and with them the managers' performance bonuses.

Is this an example of good management? The company is less sustainable and less solvent; its products are of lower quality and the knowledge used in production is degraded and outsourced. However, the company's market value increases.

Even our old medieval merchant would be horrified: the company, through which he organizes his little parcel of social work, is more indebted and more dependent on external suppliers in fundamental areas; moreover, it is more fragile in the face of changes in demand and weaker in the face of possible competitors. Seen from its perspective, the company has fallen into the lion's den: its future will depend on funds and banks that it does not control.

Between the old medieval merchant and the consulting firm, we would pick the merchant. At least his interests, and therefore his way of reading balance sheets, was about developing the productive capacity of the company and consolidating its existence.

So let us return to double-entry bookkeeping and look for in it, step by step, what our merchant would be looking for. On the one hand we have the income statement, which tells us about the company's capacity to generate profits, on the other the balance sheet, which - from his point of view - tells us about its capacity to make payments. Between the one thing and the other, he will try to answer the big questions of the business.

1. Does it work? Is the business viable?

The answer, from the point of view of our medieval merchant, is simple: does revenue exceed expenses?

The first thing we need to figure out is whether the gross profit is positive.

If it is, that means that the business itself is working. It means that we are selling our portfolio of products for more than they cost us.

If the answer is no, in a second analysis we could study separately sales and cost of sales by line of business. The main question that we would seek to answer, however, in each line of business that we study would still remain the same: that is, does it produce a positive gross profit? Do I sell what I produce in each line of business for more than the cost of the elements I use to produce them?

The second thing that we need to figure out is whether the profit I make on sales has the capacity to cover all operating costs, including outside suppliers? The answer is positive if the operating income is positive.

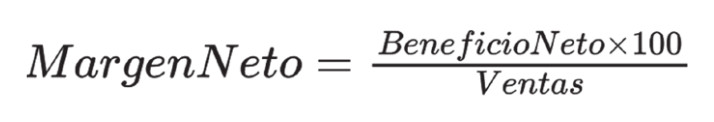

In that case, our merchant will also want to know the ratio between the profit earned and the sales made, the net margin. In order to calculate it, all we need to use is a very simple formula that will give us what percentage of the amount generated by sales becomes profit.

2. Is it a stand-alone business or a form of outsourcing under another name?

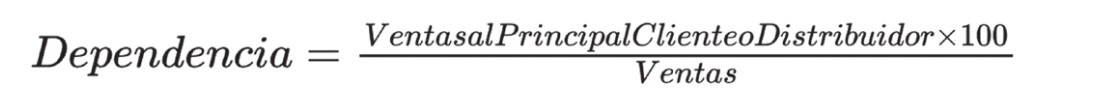

An important measure that we can use to understand the fragility or strength of the business is its degree of dependence on its main customer, a group of customers with similar behavior, or a distributor. To do this we first need to calculate the percentage it represents of total sales.

A percentage of dependency that is higher than 70% is a direct and immediate danger for any business. We would then be dealing with the power of a monopsony (purchasing monopoly) wielded over us and thus equipped with the capacity to reduce our net profit margin to a minimum... and even make us work at a loss. In other words, the surplus would be very fragile in the face of the power of a single customer or distributor.

3. Is the profit generated by the business or through the decapitalization of the company?

How large of a role does extraordinary income play in producing a profit margin before interest and taxes? Does it play a substantial role? Does it cover up a negative or very low gross profit margin? If so, in reality we would be dealing with a company in losses that is selling fixed assets in order to cover up holes and fake a level of profitability that it does not have at the cost of decapitalizing itself, surely by selling property, machinery, etc.

4. Are we dealing with a financialized company?

In every speculative bubble, the plague of financialization reappears. Companies maximize cash, selling even below cost, in order to invest hard cash in short term speculation and improve pre-tax profit.

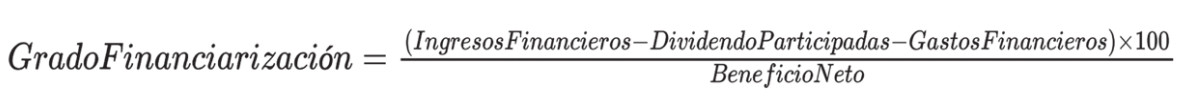

The first sign of this, provided speculation is producing profitable outcomes, is if the PBT (Profit Before Taxes) is significantly higher than the EBIT (Earnings before interest and taxes), that is, if the financial aspect of the business is responsible for a large part of the total profits.

However, there are other factors to take into account. Fundamentally, we have two sources of financial income:

- dividends distributed by investees

- income from stock market speculation, dividends from listed companies, and financial products.

Thus, in order to calculate the degree of financialization of the company, we must subtract the dividends of the investees from the financial balance sheet.

A 50% level of financialization would indicate that the profit the company obtains by selling its products is equal to what it obtains through investment and speculation. But the level of financialization doesn't even have to be that high in order to raise alarms.

In general, if we are dealing with a level of financialization that is higher than 10%, we would have to look a little closer at the numbers. Because if a relevant amount of the profit of the company is being generated through dividends from shares bought on the stock exchange, short term investments, complex financial products, stock market shares, speculation in raw materials, etc., we are dealing with a financialized and therefore fragile company. It is quite possible that the production processes and prices themselves have already been deformed and subordinated to the objective of maximizing profit through speculation.

But what happens when the balance sheet of the company demonstrates a positive outcome not due to speculation, but rather because of the effect of the investees? In this case, we must investigate the relationship of the investees to the company, and figure out whether they are also its customers or suppliers. If so, this level of dependence would not in itself be negative for the wellbeing of the company. On the contrary, we would be looking at a manifestation communicated through the balance sheet of an industrial group in the making.

If, on the other hand, investments made in other companies are unrelated to the activity of the company in question, what we would be dealing with is a very solid patrimony linked to a company which, in reality, has nothing to do with that patrimony. In a normal company, such a situation would lead to the creation of a new company in charge of managing this equity, the very existence of which would reduce risks for the owner.

In our world, the situation is different. In Spain, worker cooperatives lose their tax benefits if they own more than 10% of another company. If the company in question is integrated in the productive process of the cooperative or serves to expand their core business, the tax law allows the cooperative to own up to 20% of shareholdings of that business. So the question arises from the very moment of evaluating whether or not to participate in a new company: can the cooperative create new products to sell to its investees or can it create products with them jointly, taking advantage of the proximity?

5. And in the case of operating at a loss...

If the company is operating at a loss, our merchant will strive to figure out where they occur. His first instinct will be to quickly determine whether the losses are due to the dynamics of the business itself - that will be the first thing that he looks at - or whether they are cyclical, i.e. whether they are due to extraordinary expenses or financial expenses.

If they are due to extraordinary expenses, the problem may be cyclical or the result of the closure of an unprofitable line of business. It would be necessary to investigate further, but in principle it does not necessarily indicate a fragile company or a business in trouble. If the origin of these losses lies with the financial expenses - repayment of credits - our merchant will look at the balance sheet to determine how long the burden will last, whether the apparent over-indebtedness is sustainable and how to get out of the stranglehold.

If, on the other hand, the losses hit the core of the business, the diagnosis should focus on three sets of questions:

- Can sales be increased or is the demand simply not sufficient or accessible enough for what the company offers?

- Are the profits too low to support the costs? Can they be increased by raising prices without losing too many customers? Can they be improved by reorganizing the work or applying a particular technology? Would it be profitable to invest in this new technology? Within what time frame?

- Are overhead costs too heavy a burden on the whole, and can they be reduced?

As we can see, all of the merchant's questions are aimed at recovering or improving profits by reducing costs. This means reducing costs of working hours and material resources.

Therefore, in a worker cooperative, the three groups of questions also should include a fourth one:

"To what will we devote the surplus hours and resources gained from the reorganization of the company?"

6. Profitability

But the medieval merchant will not be satisfied by the results of this exercise. For him, his companies are nothing more than the crutch of his capital. What matters to him is not only that they produce profits, but that they produce enough to justify the fact that he invested his capital in it and not to another enterprise.

That is why the first thing he needs to calculate is the profitability of his capital, i.e. the ratio between the profits it produces and the assets invested in it, assets that can be found in the balance sheet.

Our merchant's objective is to improve or at least sustain his profitability. So when sales fall, in anticipation of a drop in net income, our merchant or his manager will feel an immediate urge to reduce assets: pay off third-party debts to the company as soon as possible, reduce inventories and stockpiled raw materials, etc.

The modern manager, that of the era of financial capital, will always feel this impulse and not only in the follow-up to a crisis. His permanent objective is to make the company attractive to large capitals in search of a destiny. Given that the objective is to maximize shareholder value, the manager will seek to keep assets at a minimum. Hence the introduction and later imposition throughout three decades of Just-in-time logistics, where warehouses were reduced to the point of becoming anecdotal... an imposition that lasted at least up until the trade war, later the Covid pandemic and afterward the war in Ukraine, had demonstrated the extent to which the radical reduction of stocks of components and raw materials weakened not only individual companies, but entire global production chains such as the automotive industry.

The level of profitability is another key source of information when it comes to borrowing and financing. From the point of view of the merchant, it is dangerous to borrow at a interest rate that is higher than the return on his own capital.

Is this the case with a worker cooperative, association or social project? No, and for good reason.

- The objective of any non-profit project is to satisfy a need and to be viable and in some cases to expand the common patrimony (the commons), not to maximize the profitability of the accumulated investments. Realizing this objective - building for example good working spaces or day-care centers for the members or workers of the cooperative - tends to result in a significant part of the surplus accumulating in the form of fixed assets. This being the case, is it advisable to liquidate these assets or place them in a holding company that will rent it out to us just so that we can improve a useful indicator for investors?

- For most social projects and small cooperatives, taking out credit means putting assets held in common at a level of risk that goes beyond the scope of the specific activity to be financed. A current asset that is convenient and readily available for the use of the cooperative or organizers of a social project makes it possible to auto-finance projects at zero cost. That is why reserves were invented.

Therefore, the larger, more mature and more solid a worker cooperative, a non-profit association or a foundation is, the lower its profitability will generally be... even if the surpluses generated by its activities on the market are ample.

Does this mean that the profitability criteria should not be applied in any case?

It certainly does not make sense to apply the criteria for the organization as a whole. No worker cooperative can do so without its logic becoming distorted, and no association or foundation is going to compete to attract capital as if it could issue or sell shares.

The specific lines of products, activities, and services offered to the market are another matter. These activities, products, and services will almost always be financed with the internal resources of the organization. Therefore, it makes perfect sense to incorporate their level of profitability into the analysis. However, the question of their profitability needs to be approached from a very different perspective from that both of the medieval merchant and the consultant.

The point is that even if the profitability of a product, service, or activity is low, or even if it does not generate losses - or even if it generates small losses - its continued existence in the catalogue can be justified for a variety of reasons that can range from the personal development of the members to the social impact of the product.

If a specific line of business in a normal company has an insufficient level of profitability, it is eliminated or reduced, thus leading to the slashing of overhead expenses at the cost of laying off workers or reducing their paid working hours. In a worker cooperative the decision to maintain an unprofitable line of activity may be perfectly rational if there are no clear alternatives to cover the working hours employed by the low-profit line of activity. For a worker organization, profitability is subordinated to the need to not reduce the number of members or their welfare.

In a worker cooperative if one chooses to accumulate savings in order to increase overall profitability, specializing in the most profitable segments instead of maintaining existing activities in the short term or diversifying (i.e., increasing scope) in the medium term, the result will almost certainly be a loss of quality of life for everyone.

7. Solvency

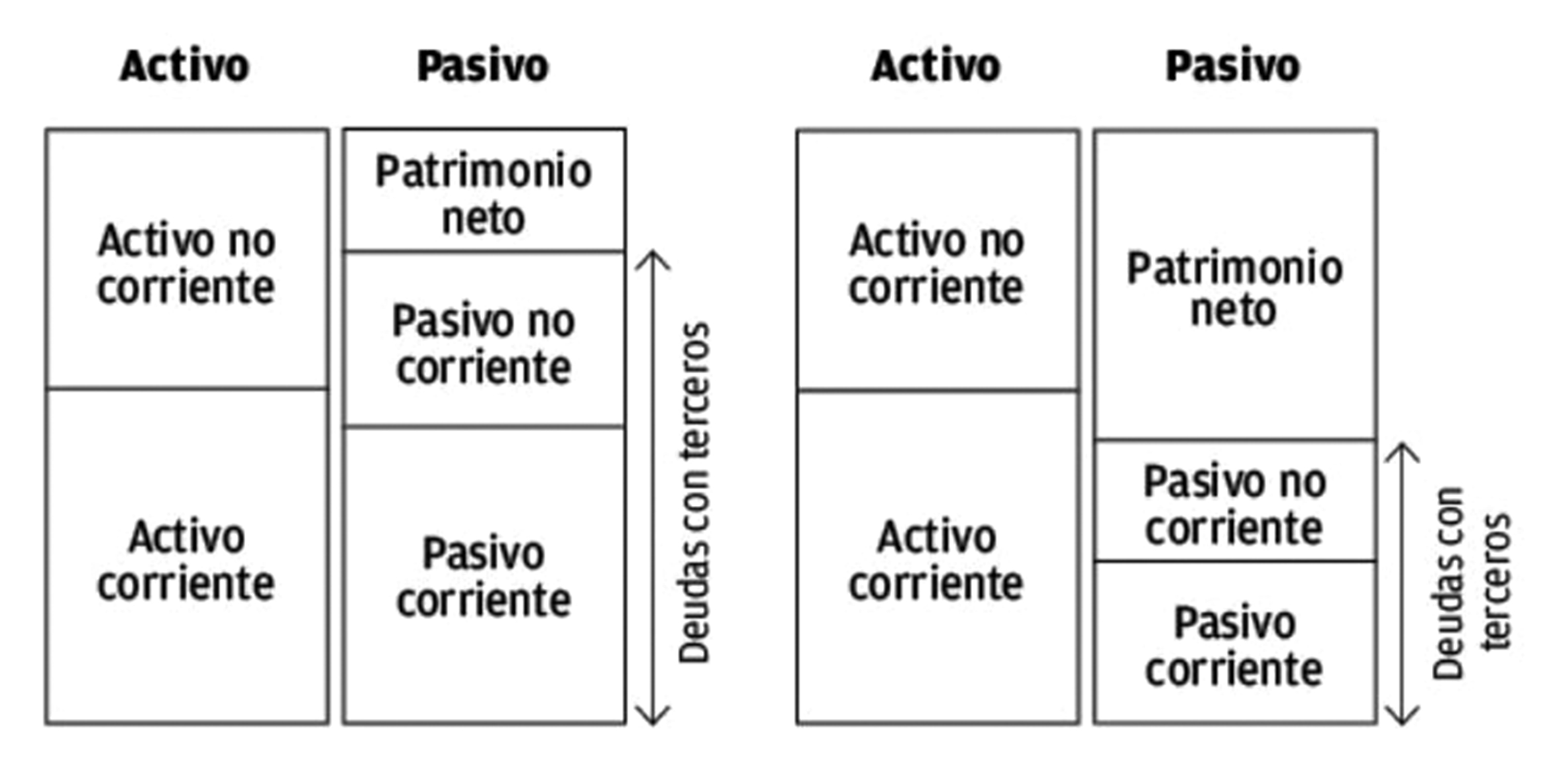

Let's continue to make the most of the balance sheet. In the following example we compare two companies with the same asset structure: they have the same resources. However, the structure of their liabilities is very different. In the first graph, liabilities are much higher than equity. Equity is, in short, what belongs to the shareholders. In the second graph, there are just as many liabilities as there is equity.

This means that the first company sustains its activity through credits while in the second company the contribution of the partners is as important as the debts acquired. If things started to go wrong, a person who had lent to the first company would have to assert their collection rights against many more debtors. It would therefore be more likely that they would have to deal with delays in payment or default. The second company is thus more solvent.

The first company, which is managed by the imaginary consultant mentioned earlier, would be a riskier client for the cooperative. If things go badly for the first company or if it is acquired by a larger company, the cooperative would likely experience more problems getting paid than if it were to have the second company as a client.

What particular thresholds are typically considered solvent in the liability structure? Our merchant would likely require 50% equity, if not more, before lending. Our consultant would probably recommend growing on credit quickly by reducing the weight of equity to 30% or even less, depending on the activity and dynamism of the company.

It is always useful to carefully review the liabilities of any corporate client, which is something that we can request from the commercial registry.

Many typical accounting practices are based on the need for companies to be able to demonstrate solvency to banks. For example: converting member loans into capital increases so that they be turned into equity; including in the balance sheet only the VAT payable as debt instead of the VAT charged; paying salaries a couple of days before the end of the month to reduce the debts with workers that appear in the balance sheets, which are generally drawn up on the first day; etc.

On the other hand, in many small worker cooperatives there is practically as much equity as there are liabilities. This is irrational in the eyes of the merchant or consultant, but undoubtedly the best and most solid guarantee of independence and soundness that they can possess.

8. First approach to the treasury: working capital

Working capital is the difference between current assets and current liabilities. That is, between what we expect to collect in the short term and what we must pay during that period.

So if the working capital is negative... we will have liquidity problems in the short term. Although not only in that case. A positive but relatively scarce working capital will not be enough to avoid delays in payments if the time it takes to collect a sale and the time it takes for supplier invoices to be paid are not in line with each other. Or simply if production is seasonal and we accumulate all purchases for the year on one date but we produce sales throughout the entire year.

It is due to the need to reduce dependence on working capital - and in financialized companies, for speculation to be carried out during the time between collections and payments - that customers are required to pay within a shorter time frame than that in which administration departments take to pay their invoices to suppliers.

An extreme case is that of tour-operators: they charge for vacations in cash months in advance but pay most of their suppliers nine months after the service has been provided. Large supermarkets also have little working capital for the same reason: they ensure a rapid turnover of products and pay after 90 days or more in order not to release a penny until the product has been sold to the end consumer. It goes without saying that tour operators and department stores were two highly financialized sectors that suffered heavily from the 2009 crisis.

Self-financed small businesses and cooperatives, those that have never had cash flow problems or difficulties in meeting payments, may find themselves in a bind when a major investment is made, such as buying premises or renovating a machine. How do they recover liquidity with a loan without further worsening their capacity to carry out short-term payments? Normally by resorting to a long-term loan, at least partially. Current liabilities remain unchanged, non-current liabilities increase and cash is increased by the same amount as the loan received. Result: working capital is restored.

Successful worker cooperatives, just like micro-SMEs, usually have very ample working capital insofar as a large part of the surplus is accumulated in assets pending productive investments or purchases of fixed assets. It is therefore difficult to have cash flow problems in worker cooperatives or micro-SMEs.

Accounting for commoners

Accounting is an extremely useful tool to understand how a company behaves in relation to the objectives of its managers and shareholders, as well as understand its solvency when it comes to paying suppliers and creditors in general.

For the same reason, in a worker cooperative, this analysis requires nuance. It is not good to buy the ideology implicit in it. For the investor or entrepreneur the company is a business, a way to maximize the profitability of the capital invested in an empty machine used to organize a small parcel of social work. The company, according to him, as accounting documents demonstrate, has nothing of its own: it owes everything to creditors and owners.

For the members of a worker cooperative, the structure that binds them together is much more than a business. Not only because it may have many different lines of production that go to market and that are completely different in nature from each other. The most important thing is that for the cooperative members, the company is not an empty and temporary structure, but rather the container of everything they share in common. Therefore, the objective - to preserve and expand the commons and its activities- cannot be measured by the profitability of the total capital employed.

That is the real meaning of the epithet non-profit of some cooperatives and of all foundations and associations. The cooperative law states that non-profit implies that the contributions -in money or other assets- of the members to the capital stock will not be remunerated. In fact, the same law states that if a member leaves a cooperative, he/she will be reimbursed for what he/she put in, but updated only with the legal interest rate of money. There is no creation of value for the shareholder possible because we are not members of a company with capital divided into shares, but rather of a working organization...

However, even if we analyze return on invested capital only to a very limited extent, other elements revealed to us through the balance sheet and income statement, such as the ability to meet payments or the strength and profit margins of our revenue streams, are crucial.

It is hard not to learn, from even a cursory accounting exercise like the one we carried out today, how to improve the efficiency of cooperative work for the objectives we set for ourselves. Insofar as we are obligated to sell our work or the result of it in the market to satisfy the needs of the working community and its environment, we can freely reject the logic of the consultant, however, we cannot abandon the world of the old Mediterranean merchant. There are a few things that we can learn from him.