Collective Interest Cooperatives and Steward Ownership Models

The SCICs (Cooperative Societies of Collective Interest) in France, the «Steward Ownership» models in Germany and those based on «Assets in Common» in the USA are the spearhead of a new productive cooperativism in which workers share or cede ownership to other agents.

A step beyond worker cooperativism?

SCICs (Collective Interest Cooperative Societies)

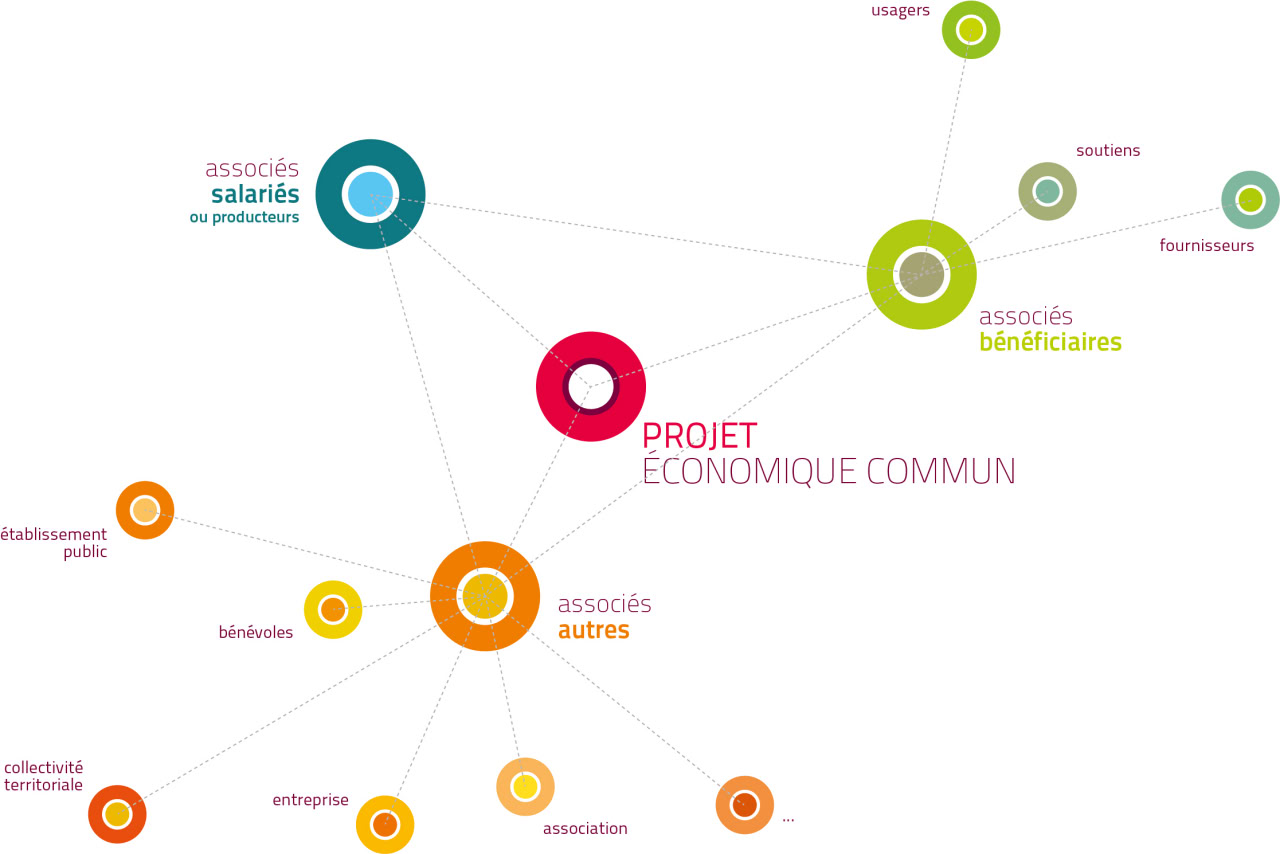

SCICs are organizations in which ownership is necessarily shared among at least three types of actors:

- Workers or independent “producers” (farmers, animal husbandry farmers, artisans, etc.).

- Beneficiaries (clients, suppliers, volunteers, collectives of all kinds, etc.).

- A third type of partner depending on the needs and objectives of the company (social groups, private companies, financiers, local administrations, etc.).

They are designed from the outset to involve local governments and broaden the cooperative base to include consumers and clients. Local governments can become members and hold up to 50% of the capital. In principle, all members, whether legal or natural persons, have equal voting rights, but members can be grouped into “electoral colleges” in the Board. The colleges, regardless of the number of members that each one has, have their votes weighed according to a prefixed percentage that oscillates between 10 and 50%, established beforehand in the bylaws.

Although the voting system is corporate, capital is remunerated on an equal basis: each euro of capital receives the same amount of return and the cooperative can allocate up to 42.5% of surpluses (net of the return of public aid) to remunerate the capital contributed by the members.

In other words, the SCIC is basically a consumer cooperative -usually made up of worker partners- and conceived as a tool to incorporate funders, municipalities and regions to rescue or kick-start companies and infrastructures of regional or local interest. The cooperative that protects the soccer club in the series “La Fiebre” is a SCIC.

Steward Ownership

Purpose Stiftung gemeinnützige GmbH is a German foundation founded in 2016 to provide a solution to the problem of succession in small and medium-sized industrial companies. The central premise is that the “Verantwortungseigentum” (literally “Responsibility Ownership”) can provide the solution. Verantwortungseigentum is a concept that, after it was translated into English as “Steward Ownership”, has turned into a global brand.

It is a model in which the company is equipped with governing bodies similar to those of a foundation and is based on the idea that companies should be guided by a “long-term objective” in which capital and labor serve as means subordinate to that objective.

The “helm” of the company (voting or political rights) remains in the hands of people who are intrinsically linked to its objectives and purpose (“stewards” or “custodians”) with the capacity to steer it with an intergenerational outlook, and which take into serious consideration the needs of the various stakeholders.

The election process of the “custodians” is quite reminiscent of that of the board of directors of so-called “Bavarian capitalism”.

The role of stewards is also defined by their direct link to the business: although many are internal and active in the company (founders, workers, managers), some companies choose to integrate independent people into the organization in order to have a diversity of perspectives. These external custodians are usually well versed in the industry, backed by years of experience and a successful entrepreneurial spirit. Representatives of key stakeholders may also sit on such a board.

According to the Purpose foundation, the significance of this lies in shareholders “no longer having the power” and being considered as merely another investor which, despite receiving remuneration, having the capacity to influence, and having their needs taken into serious “consideration” by management, lack political power in the company.

Assets in Common

In the USA the model was provided by the consulting firm Common Trust, which launched along with the Purpose Foundation the project Infrastructure for Shared Ownership. From this project came in turn the book Assets in Common, widely sponsored by the Purpose Foundation, and which occupied space in magazines such as Shareable. It might be surprising that the latter included this sponsored content in the section on cooperativism, but the focus of Assets in Common is more open than that of “Responsible Ownership”.

Incorporated in the catalog of models of Assets in Common are models of cooperation between owners, internal currencies for networks of companies and even systems in which worker cooperatives are created for specific tasks without real autonomy within the structure that controls the trust characteristic of the original German model.

Is this a step forward towards a social model or step back towards corporatism?

Was an alternative to worker cooperativism needed?

What these three models have in common is that they define themselves as an alternative that can overcome worker cooperativism rather than as an alternative to or an overcoming of the dominant share-ownership model. This is striking because it does not seem sensible to claim that the collective ownership of workers over the enterprise in which they work is a problem that needs to be resolved.

SCICs, management, investors and managerialist models

In the case of France, the cause can be traced back to its origins. SCICs emerged at the end of the 1990s in France as a way to recuperate enterprises hand in hand with the state and private investors.

It is not a bad cause, but it is put forward in a way that expresses the general tendency of the ICA to denaturalize worker cooperativism - hegemonic in the country up to that time - and opt for models that facilitate the managerialization and dilution of worker ownership.

It is not for nothing that the SCIC was the laboratory of a model of dilution of worker cooperativism in the countries where it was the protagonist which, later on, was exported to countries such as Costa's Portugal, where worker cooperativism no longer even exists as a legal form of its own.

Steward Ownership and the recuperation of industries... by independent managers

"Steward Ownership” was born as a way to ensure the continuity of German SMEs after the retirement of their founders. But if you think about it, there is no succession problem in the German business fabric: companies are usually easily sold to investors - often foreigners - or to the employees themselves.

The Purpose foundation does not argue that companies should not be sold to foreigners - at least not in writing - but it competes with cooperativization initiatives by proposing a succession guided by the idea of purpose. We will not talk about it because the purpose very seldom consists of anything other than the continuity and satisfaction of all parties involved in the company, i.e., nothing concrete.

And in fact the foundation expressly targets its message towards the owners of worker cooperatives, i.e. the worker-members, by arguing that the "Steward Ownership" system is a way for worker cooperative members to sell their cooperative to a multinational or investment fund to make personal cash. It does not exactly ooze idealism, it rather it seems like an attempt to entice workers to hand over ownership to independent managers who have become the custodians of an empty purpose.

“Assets in Common" emerged through the competition with cooperativization.

The consulting firm Common Trust, which adapted the German model to the U.S. by creating Assets in Common, summarizes its focus on the front page of its website:

We help owners design and execute a sale to a customized trust that is run by key stakeholders and experts, while getting cash out on day one. This method is much cheaper than an ESOP and offers competitive sale pricing, tax advantages, long-term upside and perks for management.

An ESOP is an employee stock ownership plan. That is to say that the model is intended to be an alternative to the cooperativization of companies when their founders want to retire.

Is this a broader form of cooperativization or plain old corporatism?

There is another element in common in all these new models: their resemblance to fascist corporatism and the idea that opposing interests can be reconciliated through the organic subordination of the interests of all to the common purpose of the permanence of the enterprise.

Let us turn to the French model: why would a multi-agent SCIC be better for ensuring the continuity or the initiation of an economic activity than a second-degree cooperative?

In the SCIC, investors, administrations and even so-called stakeholders have their own legal entity, only the workers and consumers lack their own structures as co-owners. But it is well known that the representation of consumers, in the end, falls on management because the costs of participation of consumer members are higher than the benefits they get for participating. Consumer co-ops are the paradise of managerialization and in fact, historically, they have only maintained transparency and real social control when the members were not individual consumers but rather worker cooperatives and worker societies.

It is impossible not to see that the underlying idea is to protect the company - i.e., investors and institutional partners - from the associated workers by granting managers the role of conciliators of a diverse set of interests.

In SCIC this translates into reducing the role of workers to an electoral college with a maximum of 50%, thus reproducing the forms of the vertical unions of fascism, Francoism, etc. In the case of the “Responsible Ownership” and “Assets in Common” models, the perspective of old corporatism is explicit and does not even try to hide its identification with the Japanese keiretsu.

Can a communitarian economy be organized in a non-corporatist way?

The answer is clearly yes. Committees of established managers who act as custodians are not required to uphold the purpose of communitarian development.

One possible path, within a very specific framework, that of rural repopulation, is that of Digital Worker Cooperatives. Another, that of the Cooperative Agglomerations or Cooperative Unions that are articulated around work cooperatives as was common in the cooperativism of the socialist type of continental Europe until the World Wars. Another one, that of second-degree cooperatives, which can incorporate associations and interest groups without diluting worker cooperatives or getting them to give up their sovereignty.

And in the case of recovered or rescued enterprises, such as Duralex in France, nothing prevents a cooperative from taking public and private credits by agreeing on rules for the distribution of surpluses which, as long as it does not repay the principal, give primacy to its creditors within sensible margins.

No shortcuts

In fact, there is no way to organize a truly inclusive, transparent and participatory communitarian economy that does not place worker cooperatives at the center. Anything that terms itself "communitarian" that falls short of that constitutes an affront to the term and necessarily leads to managerialism and the nourishment of the social attitude that sustains it: passivity.

Neither counterweights nor trustees can build community or communitarian economies. There are no shortcuts on the road to democratic, resilient and resistant local economies.